In September 2023, the NAO team sent several samples to the MIT BioMicro Center, for library preparation and sequencing using their new Element AVITI sequencer. This machine works on quite different principles from Illumina sequencing, but also produces high-volume, paired-end, high-accuracy short reads. Since it looks like we might be using this machine quite a lot in the future, it pays to understand what it's doing. However, I found most quick explanations of Element sequencing much harder to follow than equivalent explanations of Illumina's sequencing technology (e.g. here).

To try and understand this better, I dug deeper, using a combination of talks by Element staff on YouTube, their core methods paper, and aggressive interrogation of Claude 2. Given my difficulty understanding this, I figured others on the team might also benefit from a quick-ish write-up of my current best understanding, presented here. Note that this does not go into the performance of Element sequencing, only the underlying mechanisms. Note also that, given the lack of very detailed documentation about many aspects of the process, my understanding here is inevitably more high-level than it would be for e.g. Illumina sequencing.

1. Library prep

The fundamental stages required in library prep for Element sequencing are mostly very similar to Illumina sequencing: fragmentation, addition of terminal adapter sequences, optional amplification, size selection, and cleanup. The main additional step required is circularization: to be compatible with Element's cluster generation method (see below) mature Element library molecules must be circular, with the 5' and 3' adapters joined end-to-end.

Given the similarity with Illumina library prep procedures, Element have sensibly designed their processes to be compatible with many standard Illumina library prep kits. There are two main ways to adapt Illumina library prep kits for Element sequencing:

In the first (Elevate) workflow, the standard kit protocol is followed, but with Element adapter oligos (including sample indices) replacing Illumina adaptors. The library molecules are then circularized by ligating the ends of the adapters together, cleaned to remove linear molecules, and are ready to be introduced to the flow cell.

In the second (Adept) workflow, the standard kit protocol is followed completely (including use of Illumina adapters) followed by additional steps to convert the resulting library into an Element library: addition of terminal Element adapter oligos, circularization, and cleanup.

2. Cluster generation

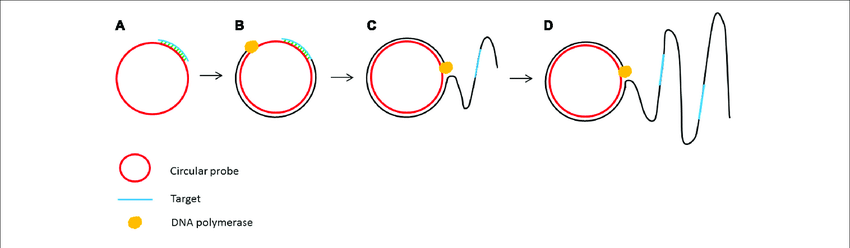

Following library prep, the libraries are denatured to produce single-stranded circular DNA molecules, then washed across a flat flow-cell studded with attached oligos complementary to the adapter sequences.

Library molecules bind to these oligos, with unbound library molecules washed away.

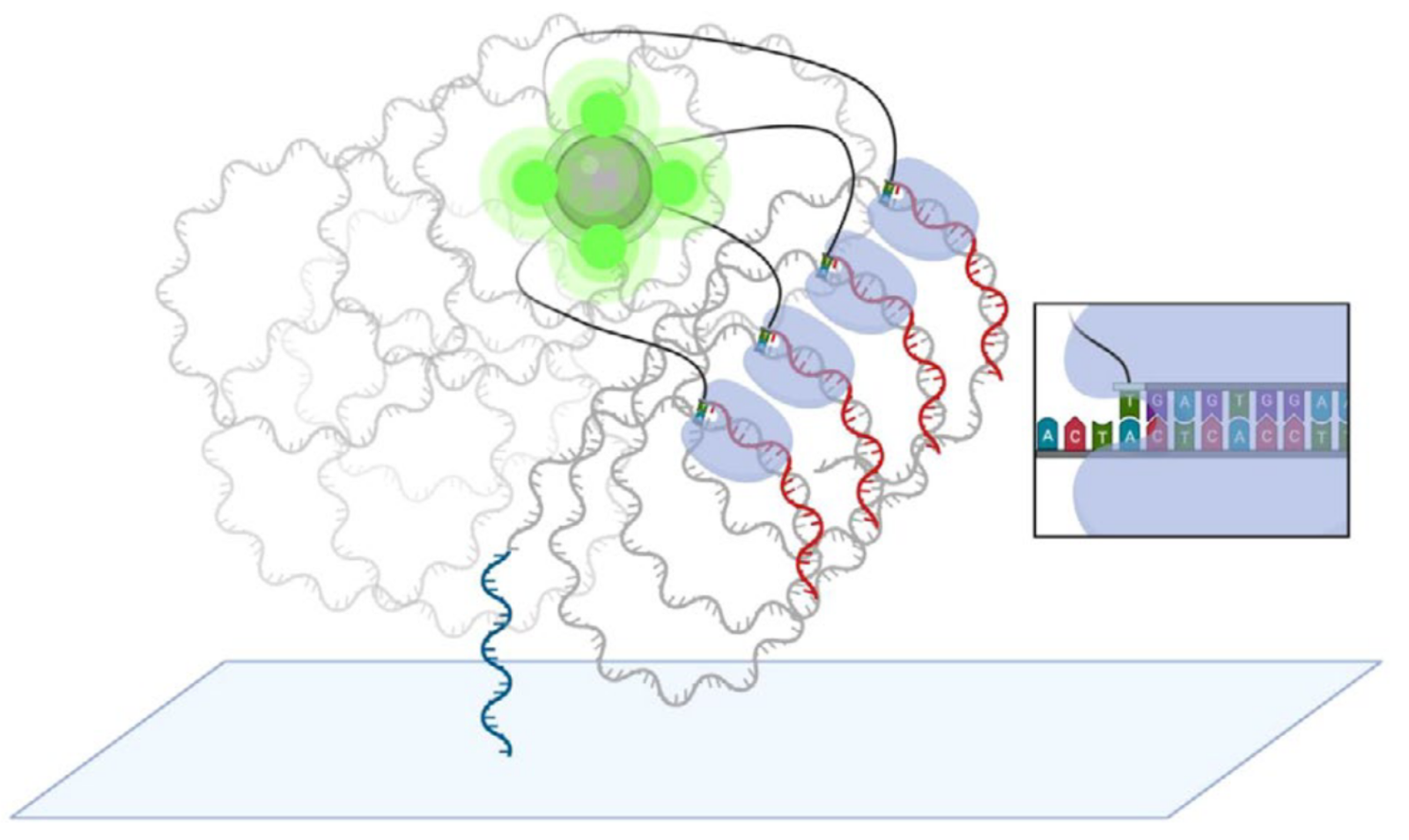

Polymerases and nucleotides are added, and elongate from each attached oligo via rolling circle amplification.

Briefly, the polymerase starts at the hybridized adapter/oligo double-stranded sequence and moves around the circular library molecule. When it reaches the end of the circle, it continues on to another revolution, displacing its own previously-synthesized daughter strand as it goes.

This continues over repeated passes, producing a long single-stranded molecule containing many concatenated copies of the (complement of) the original library molecule sequence:

Imagine this picture, but with the blue primer attached to a flow-cell at one end.

The resulting long, attached molecule is referred to as a concatemer, or polony. A prepared AVITI high-output flow-cell contains roughly 1 billion polonies, each of which corresponds to one read pair. (An AVITI run comprises two flow cells run in parallel, for roughly 2 billion read pairs per run.)

3. Daughter strand elongation

Although Element sequencing is not sequencing-by-synthesis, it is, as it were, sequencing-with-synthesis. Like Illumina, the core of each sequencing cycle is the stepwise elongation of daughter strands complementary to the library molecule sequence in each cluster, followed by imaging to determine the next nucleotide in the sequence. The mechanism of base calling is completely different (and will be described in the next section) but the stepwise elongation process is closely related.

In the case of Element sequencing, elongation begins with annealing of a sequencing primer complementary to one of the Element adapter sequences. These primers will bind many times to a given polony molecule, at the beginning of each copy of the RCA-duplicated library sequence.

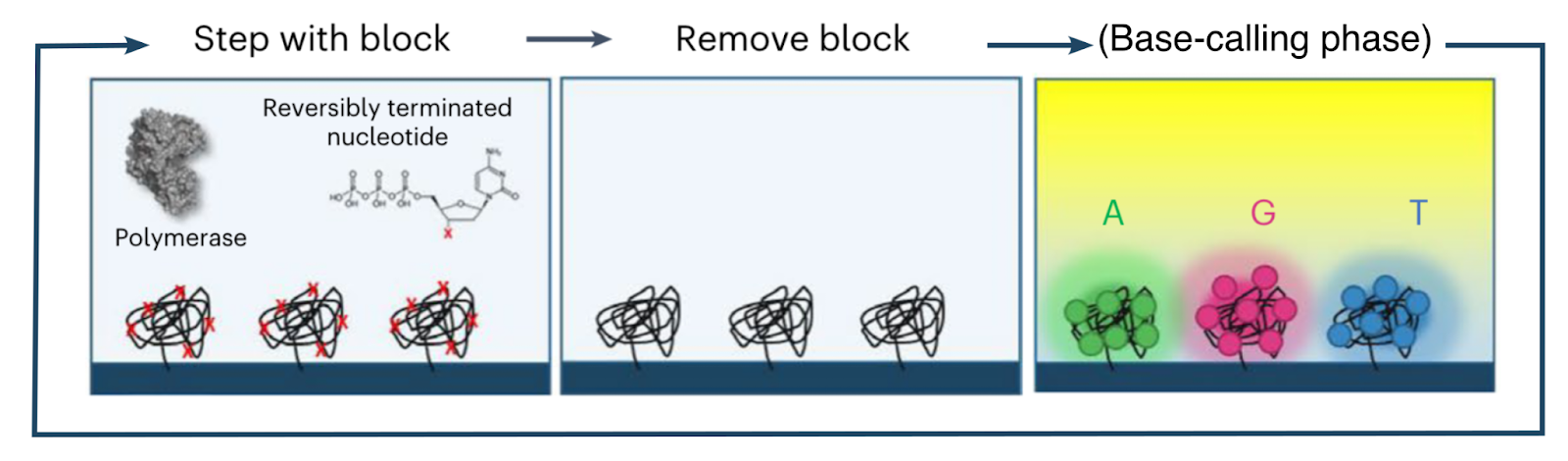

A mixture of DNA polymerase and reversible chain terminator nucleotides is then washed across the flow cell. The polymerases bind the double-stranded primer sequences and incorporate a complementary terminator nucleotide, extending the double-stranded sequence by one base pair (after which further elongation is blocked).

The polymerases and free nucleotides are displaced and washed away, after which the blocking group on the incorporated terminator nucleotides is removed (enabling further elongation). Base-calling occurs (see below), after which the cycle repeats with the addition of polymerase and terminator nucleotides.

To generate a reverse read, the same process takes place, but using primers complementary to the other adapter sequence.

4. Labeling, imaging, and base calling

- The optical generation of base calls is the most complex and distinctive aspect of Element sequencing, and the one that I had the hardest time understanding. What follows is my best attempt at an explanation, but I'm not fully confident I haven't misunderstood something fundamental.

4a. Background and justification

When a polymerase binds a DNA strand, it first positions itself over the boundary between the double-stranded primer region and the single-stranded template region. It then recruits and positions a nucleotide complementary to the first base of the template region, using a combination of base pairing and direct interactions between the nucleotide and the polymerase enzyme itself. Finally, it incorporates the new nucleotide into the elongating daughter strand by connecting it to the end of that strand via a new phosphodiester bond.

- Usually, the polymerase then repeats the cycle by recruiting and incorporating a nucleotide complementary to the next base of the template strand; however, if the incorporated nucleotide is a chain terminator, it is unable to do this, and stalls.

In Illumina sequencing, the terminator nucleotide incorporated by the polymerase is fluorescently labeled, and is imaged following incorporation. The fluorophore is then cleaved off along with the terminator group, and the cycle repeats. As a result, the process of daughter strand elongation and base calling are closely bound together.

In Element sequencing, the goal is to separate the processes of daughter strand elongation (above) and base calling, so that the two can be optimized separately. To achieve this, the aim is to call the next unincorporated position in the template sequence, rather than (as in Illumina sequencing) the most recently incorporated position.

One theoretical way to do this would be to use an engineered polymerase that is able to recruit complementary nucleotides but not incorporate them. One could supply this polymerase with fluorescent nucleotides, and it would recruit the one complementary to the next position on the template strand. This would occur simultaneously at many different locations on each polony, corresponding to the different copies of the library sequence produced by RNA. One could then image the flow cell to identify the nucleotide type recruited at each polony.

The problem with the above approach is low signal persistence. Without incorporation, recruitment of nucleotides by the polymerase is weak and transient: the nucleotide binds its complementary base and the polymerase, remains for a short time, then dissociates. The result is that, for any given polony, too few nucleotides are recruited at any one time to give a sufficient signal for imaging.

In order for an approach like this to work, then, we need a way to improve signal persistence without relying on covalent incorporation of nucleotides. Enter avidity sequencing.

4b. Base calling by avidity

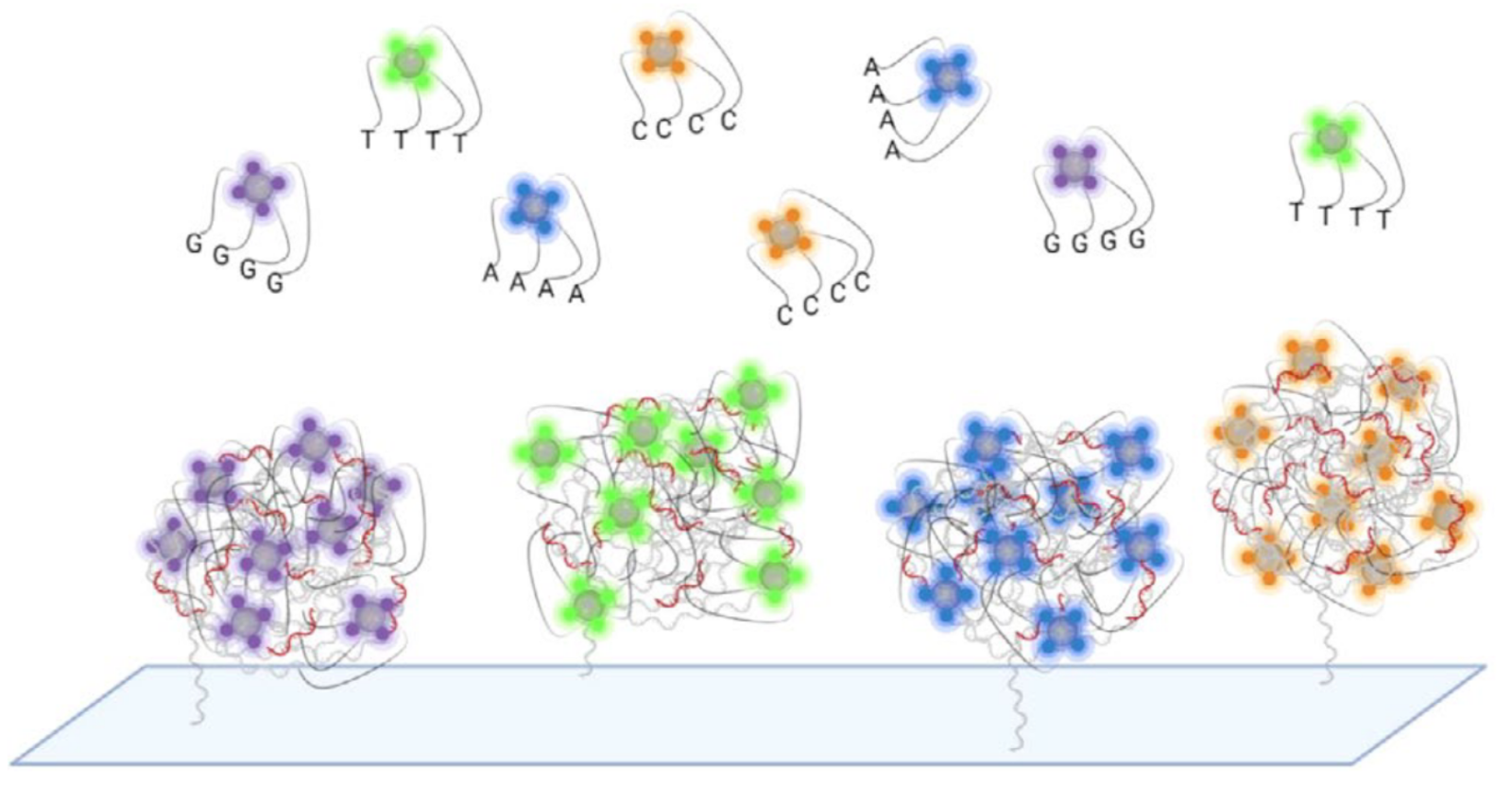

The avidity of a molecular interaction is the accumulated strength of that interaction across multiple separate noncovalent bonds. Even if any single one of these bonds is weak and transient, the overall interaction can be strong and stable if the two molecules interact at many different points.

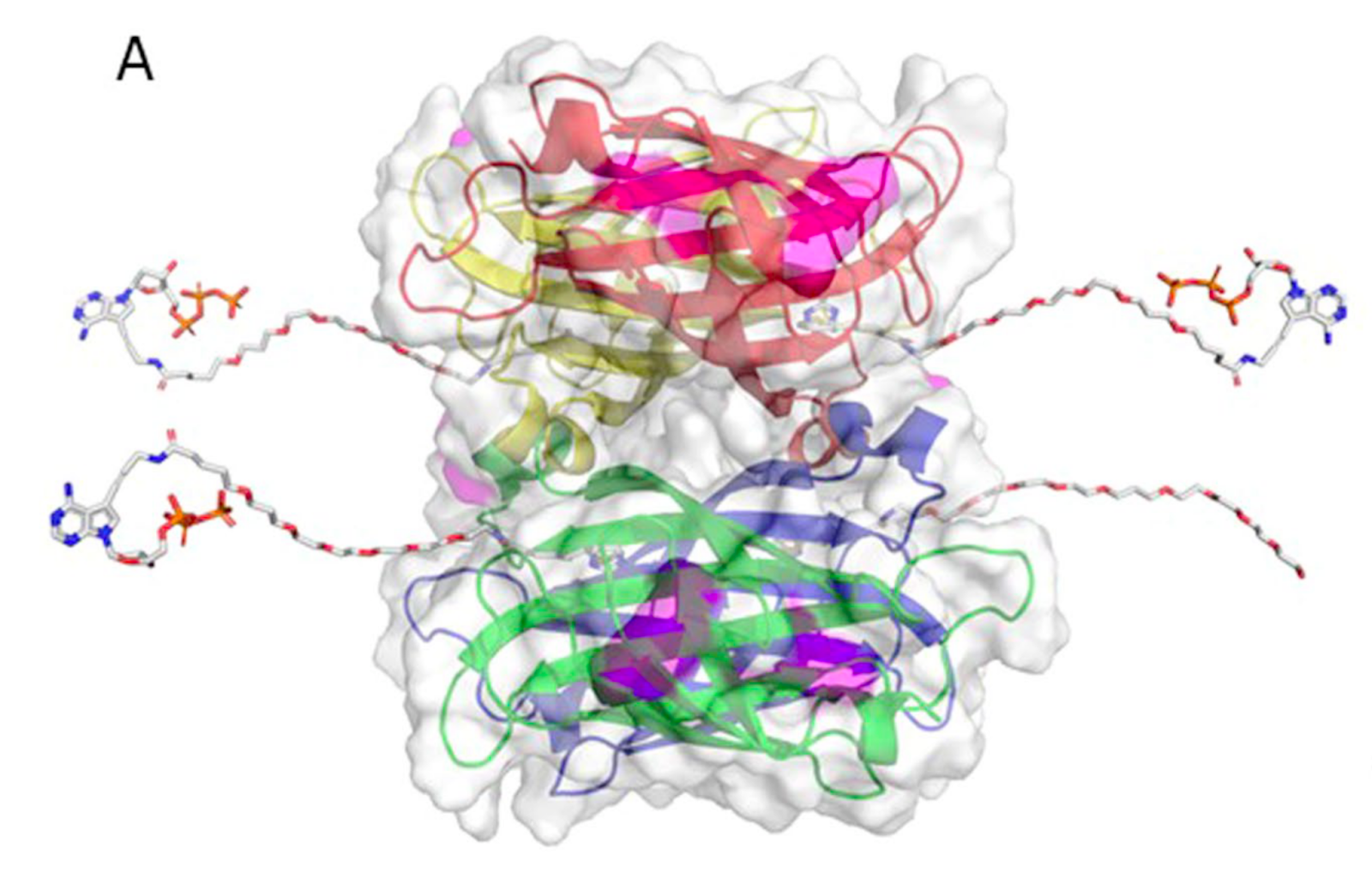

In Element avidity sequencing, the avidite is a large molecular construct, comprising a fluorescently labeled protein core connected to some number of (identical) nucleotides via flexible linker regions. Each of these nucleotide groups can be independently recruited by a polymerase bound to a polony, and positioned based on base-pairing interactions. While each of these nucleotide:template:polymerase interactions is too weak and transient to sustain a strong signal, the avidite as a whole is bound to the polony via multiple such interactions, producing a strong and stable interaction overall.

Example avidite structure from the avidity sequencing paper. The core of the molecule consists of fluorescently labeled streptavidin, bound to linker regions via streptavidin:biotin interactions. Three of the four linkers shown here end in nucleotides (specifically, adenosine); the fourth mediates core:core interactions to produce an even larger avidite complex.

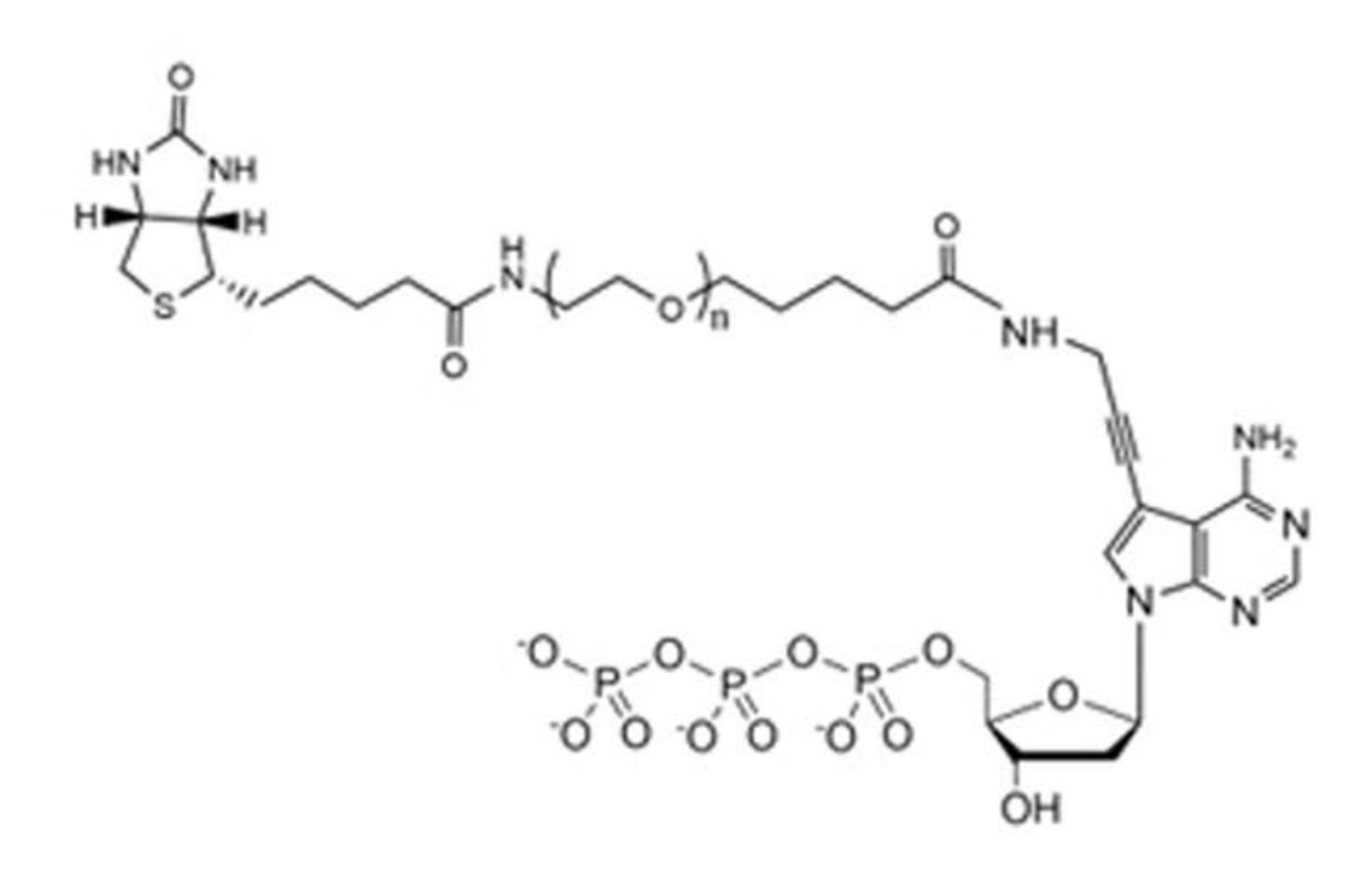

Example avidite arm structure, with biotin at one end (top-left) and adenosine at the other (bottom-right).

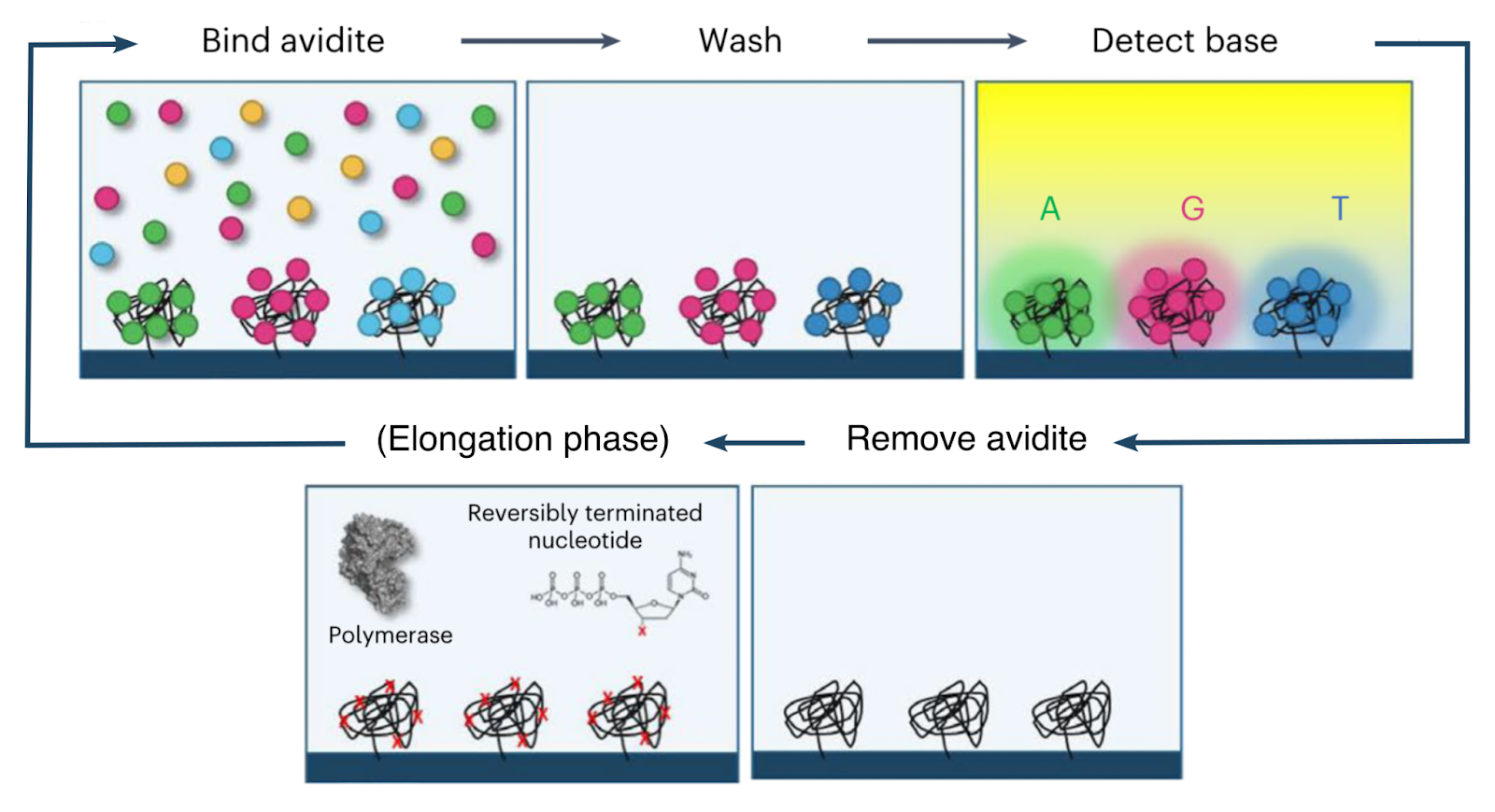

The base-calling phase of the avidity sequencing cycle thus proceeds as follows:

Prior to the base-calling phase, the polymerase and nucleotides involved in the elongation phase are detached and washed away.

The flow cell is then washed with a mixture containing an engineered polymerase as well as four fluorescently-labeled avidites (one each for A, C, G and T). The engineered polymerase (henceforth the avidite-binding polymerase, or ABP) is distinct from that used for elongation, and is capable of binding a template strand and recruiting a complementary nucleotide, but not capable of incorporation.

The ABPs bind to the double-stranded regions of each polony and position themselves at the boundary with the single-stranded template region. They then attempt to recruit nucleotides complementary to the next position on the template strand. The only nucleotides available are those attached to the avidites, which are thus recruited.

Since each copy of the template sequence in each polony is synchronized, each polymerase bound to each polony attempts to recruit the same nucleotide type, and thus interacts with the same type of avidite. Each avidite molecule is thus recruited to multiple points on the polony, producing a stable overall interaction.

Multiple copies of the same avidite molecule are thus recruited to each polony, producing a strong and uniform fluorescent signal.

The flow cell is then imaged to identify the avidite bound to each polony, and thus the next nucleotide in each read. After this, the ABPs and avidites are detached and washed away, and the cycle proceeds to the next elongation phase (see above).